The Fine Line Between Acknowledging Difficulty and Fueling Excuses

The Fine Line Between Acknowledging Difficulty and Fueling Excuses

Growing up, my dad had a knack for helping me unpack situations—from soccer games to major life events. While it could be frustrating at times, I credit him with teaching me the invaluable skill of self-reflection. He encouraged me to recognize my limitations and develop strategies to overcome obstacles, ensuring I was prepared when similar challenges arose.

My dad didn’t mince words. Whether he was commenting on how I looked in a dress for a semi-formal or weighing in on a major life decision, his honesty was always direct. As a child, I didn’t fully appreciate or understand the power of his straightforwardness. However, I always knew I could trust what he was saying, no matter how tough it was to hear.

One day, in a moment of frustration, I blurted out, “It’s not my fault—I have ADHD!” My dad’s response was clear and direct: “Some people have cancer, some people have diabetes, and that sucks. But you don’t just stop living; you figure out what needs to be done, and you do it. You have ADHD—that sucks too, but if you use it as an excuse, it will become a barrier. In reality, it’s only a hurdle.”

This lesson has stayed with me. I often talk to my children and students about the difference between a barrier and a hurdle. It’s a concrete example that helps both children and adults understand that while we shouldn’t discredit the struggles we face, we also shouldn’t allow those struggles to define us.

Another vital part of my experience was watching my dad succeed while being honest about his struggles. Although he was never formally diagnosed, it’s clear to me that he also has ADHD. Watching him earn his Physician’s Assistant Certification from Yale made it difficult for me to make excuses for myself. It’s imperative that children have role models who have achieved success despite similar struggles. Because Neurodivergent conditions are often hidden disabilities, many children may not realize that their role models share in their struggles, which can lead to excuses taking hold.

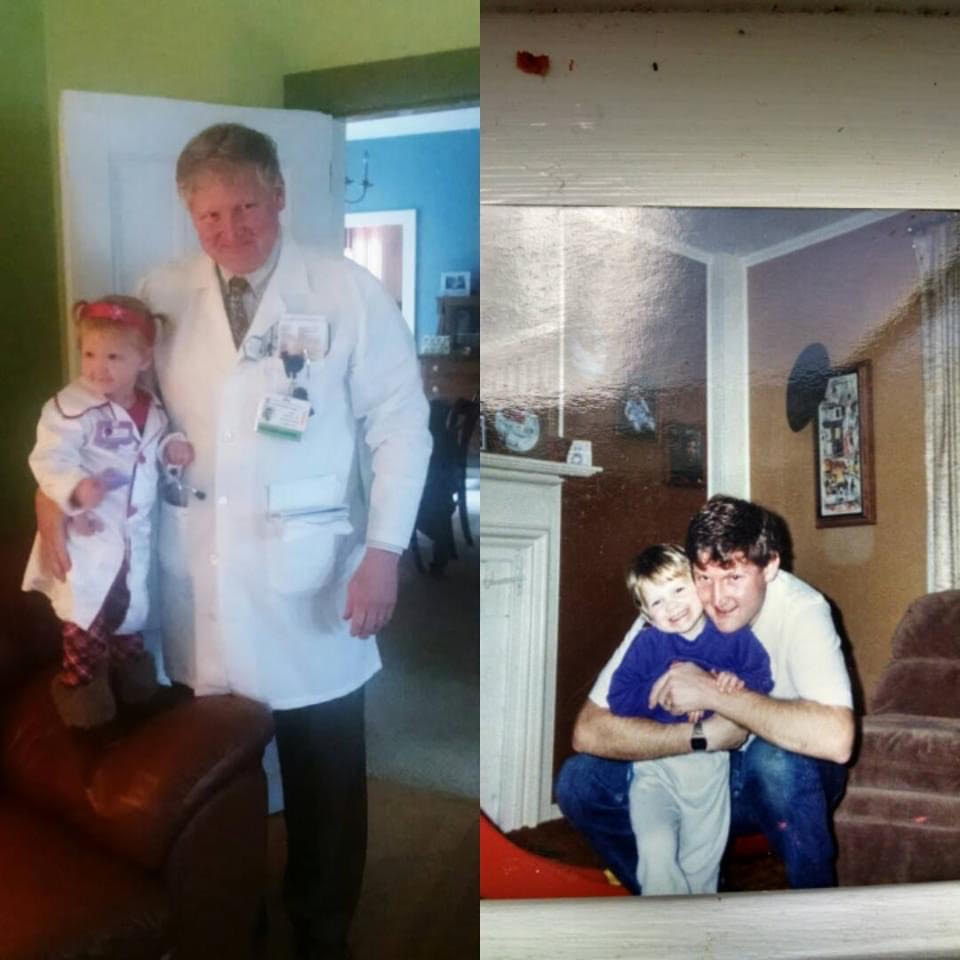

A picture of my dad and Arianna and my dad and I at the same age!

Dear Neurotypical Adult,

When working with a child who has ADHD, your approach should be twofold: validation and pivot. Validate the struggle the child is experiencing, then pivot the conversation to focus on a strategy that will help them complete the task. As parents and teachers of neurodivergent children, our focus must be on the “how,” not the “what.” If we allow children to dwell on what they can and cannot do, the list of “cannot” will easily grow. By focusing on how we do things, we acknowledge their struggles without creating or reinforcing excuses.

Help Your Child Find Safe Adults

My daughter recently switched gyms for gymnastics. In the past, these transitions were much harder because the adults at her previous gym weren’t well-versed in ADHD. They often found her to be needy and dramatic. However, her new gym has empowered my daughter to be unapologetically herself. It provides a safe space for her to advocate for her feelings and needs.

Having another adult in my daughter’s life—someone who arguably spends just as much time with her as my husband and I do—who validates her feelings has lifted a huge weight off my shoulders. Recently, Arianna felt rejected by her coach, even though from an outsider’s perspective, there was no rejection. Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria (RSD) doesn’t care about facts or reality; it’s about how she feels. But with the right support, we’ve been able to turn this into a teaching moment, giving her the tools to identify her feelings and ask for clarification.

Many people with ADHD carry trauma surrounding the idea of excuses because we live in a world where intent and context matter much more than they do to neurotypical people. When a neurodivergent person is giving context, it is often perceived as an excuse. In reality, the neurodivergent person is processing through the experience. So when Arianna can safely talk through her feelings without it being seen as an excuse, it reduces the trauma she experiences.

"I Can’t Help It, I Have ADHD"

To be honest, this phrase is often reinforced within the school system by well-meaning adults who don’t understand the difference between how we do something and what we are doing. Reducing expectations for children who experience life differently creates a bad learning environment for all children.

Last year, an uncomfortable situation occurred at my daughter’s school. A 5th-grade boy groped a female student during gym class. Ari was beside herself about what had happened; she wanted justice, she wanted the wrong to be right. The next day, the vice principal told a group of girls that it was their fault for bullying the boy, saying he “couldn’t help it.” There’s so much to unpack in that statement, but what Arianna took from it was, “I have ADHD as well, so without my medicine, I can’t be held accountable for what I do either.” She came home that night and informed me that she wouldn’t be taking her medicine the next day, that she would be handing out the punishment the boy deserved, and when the administration came to punish her, she would kindly remind them that she too had ADHD and didn’t take her medicine, so she couldn’t be held accountable for her impulsive actions.

As adults, we must be careful not to perpetuate the idea that ADHD prevents us from meeting society’s expectations.

How to Focus on the “How” and Not the “What”

When we focus on "how," the problem becomes a hurdle that can be overcome with different approaches. When we focus on "what," it becomes a barrier that seems insurmountable. This strategy works in various contexts, from homework to making friends.

For example, when a child says, “I can’t do homework, I have ADHD,” they are most likely trying to communicate that they can’t sit still long enough to focus. By addressing the "how," we can remove that barrier and try the task again.

How That Looks

If your child is struggling to focus on their work, offer alternative approaches. You might say, “I see you’re having a hard time sitting still and focusing on your work. Let’s try this another way. Would you like to stand while you work or lie on the floor? Can you do two problems, then take a break and come back to it?”

I recently saw a reel from a prominent autism advocate who referenced Dr. Seuss's book Green Eggs and Ham. The idea is that homework, like green eggs and ham, needs to be “eaten.” It doesn’t matter where or how, just that it gets done. Since our school system was designed to create compliant, orderly factory workers, giving neurodivergent brains autonomy and choices can reduce the hurdles they face.

Combating the tendency to use neurodivergence as an excuse starts with us as adults. We must avoid perpetuating the idea that ADHD is something to be cured. It’s hard not to view something labeled as a “deficit” and “disorder” negatively, but teaching our children how brilliant they truly are and how their brains work allows them to understand the power they hold.

When my son, Mason, tells me, “I didn’t take my medicine; I can’t control my body,” I respond by saying, “You can; it’s just harder when you don’t have your medicine. If you know you didn’t take it, you need to recognize that you’ll have to work harder to control your body in certain situations.”

The more we explain and provide information to our neurodivergent children, the more they will absorb and thrive. To this day, if you provide me with a reason, I’ll be better able to do what you need me to do. The neurodivergent brain seeks information and understanding. Often, when I ask questions to better understand situations, people think I’m being nosy when in reality, my brain just wants to grasp all the complexities of the situation. Even as an adult, if I know why I’m stuck in traffic, I can relax and wait patiently. However, if it’s just rush hour with no clear reason, my whole body tenses up.

By focusing on the “how” and not the “what,” we can help our children navigate their challenges without allowing those challenges to become excuses that hold them back.

Comments

Post a Comment